AI Bubble Trouble: Why Most AI Fails, and Why "Bubble Vision" Didn't

AI Bubble Trouble: Why Most AI Fails, and Why "Bubble Vision" Didn't

In the world of corporate AI, there is a pilot project problem. We have a "look at this shiny new tech" problem. What we often lack are solutions that are fully deployed, embraced by the front lines, and delivering value, day in and day out.

After eight years of building AI systems in the energy sector, I’ve seen countless projects fail. They fail not because the algorithm was wrong, but because the team fell in love with the technology before they understood the problem.

The most successful, durable, and frankly impactful AI solutions—the kind that get patented and adopted—rarely start at the computer. They start in the field.

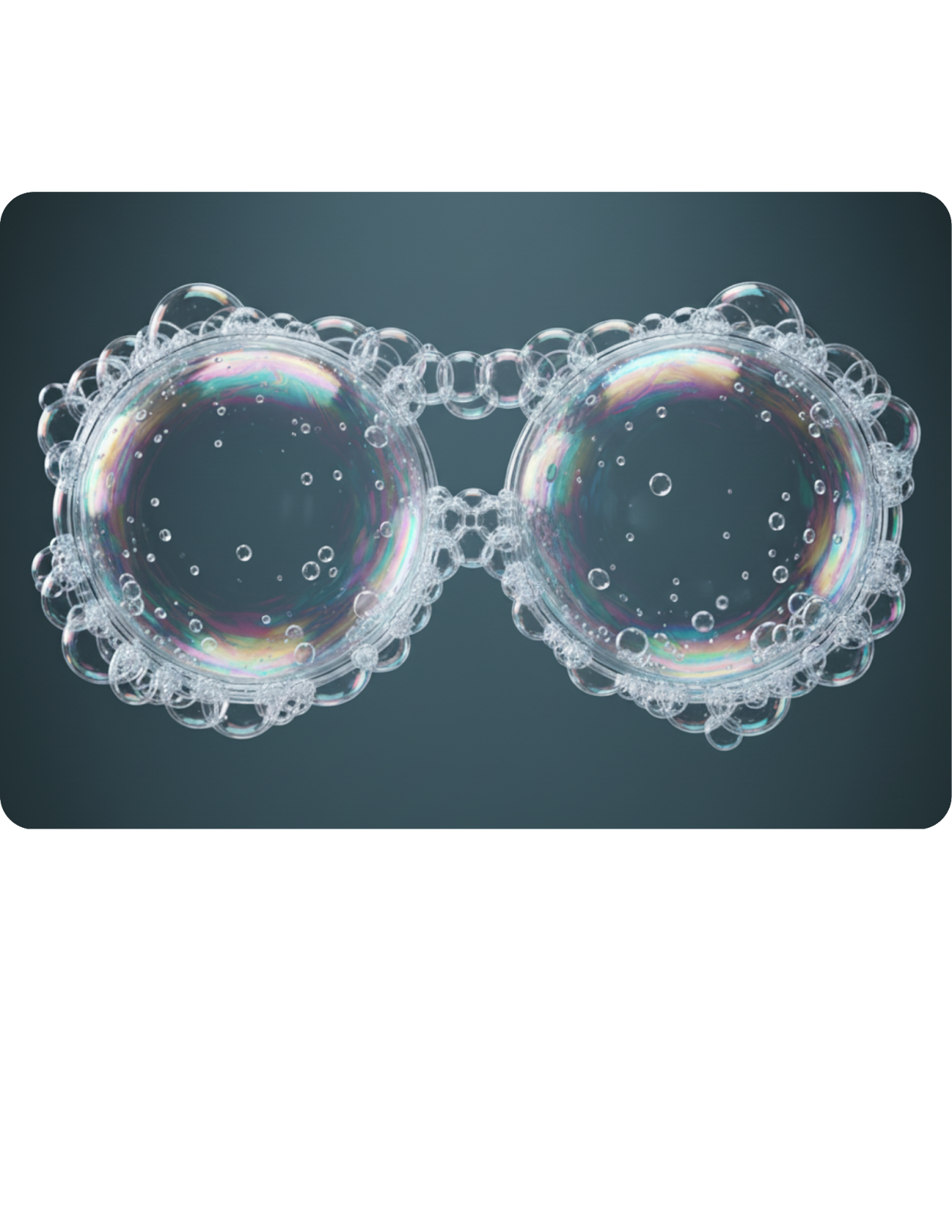

I want to tell you a story about a project I led in the energy industry. It’s a story about natural gas, computer vision, and soap bubbles. We call it "Bubble Vision," and it’s a perfect case study for the way to build AI that actually works.

The Problem That Wasn't a "Data" Problem

Our challenge, as an industry, was straightforward, yet profound: how do you accurately measure the volumetric flow rate of a natural gas leak in the field?

For natural gas limited distribution companies, this is a critical task for safety, environmental compliance, and asset management. But it’s incredibly difficult. You can’t see natural gas. You can’t cup your hands around a leaking pipe and measure what comes out. Traditional methods were focused on measuring concentration which only explained how much gas existed in one area at an instant. New technology at the time that could measure volume was inexact, expensive, and impractical for technicians.

The initial "AI" impulse would be to throw technology at the problem. Perhaps a sophisticated acoustic sensor that listens for the leak and calculates the flow? Maybe a complex chemical "sniffer" deployed on a drone?

We did none of those things. We didn’t want to add to the technicians responsibility, we wanted to better enable their current process.

Before we wrote a single line of code, our data science team did the most important thing any AI team can do: we left the office. We put on hard hats and steel-toed boots and went to shadow the natural gas technicians—the true domain experts who had been solving this problem, in their own way, for decades.

The "Aha!" Moment: From Soapy Water to a Data Source

We followed the technicians on their leak investigation routes. We watched their process. And we had an idea bubble up.

When technicians suspected a leak, they pulled out a spray bottle filled with soapy water. They would spray the soapy water on the pipe, and if there was a leak, bubbles would form.

It was a simple, elegant, and effective way to visualize the invisible. For them, the process ended there. "Yep, it's leaking." But for us as data scientists, this was the "aha!" moment.

The technicians weren't just finding the leak; they were creating a data source. Those bubbles weren't just a yes/no indicator; they were a physical visual representation of the gas escaping. The size and frequency of the bubbles were proportional to the volume of the gas.

We had found our path. The problem wasn't a "big data" problem. It was a "soapy water" problem.

Building AI That Augments, Not Replaces

We stopped thinking about abstract, complex sensors and started focusing on the technician's existing workflow. Instead of forcing them to adopt a new tool, what if we simply augmented the one they already trusted?

This is how "Bubble Vision" was born.

The methodology became clear:

- The Input: A technician performs their normal process: they spray the soapy water on the suspected leak.

- The Capture: They take a short video of the bubbles with their standard issued smartphone or tablet.

- The AI: We trained a computer vision model to process that video. The model automatically identifies the bubbles, measuring their relative size to the pipe size to estimate the volume of the gas filled bubbles.

- The Output: By calculating the total volume of the bubbles being created over a few seconds, our application could produce something that was never possible before: a reliable, field-generated estimate of the volumetric flow rate.

We had created a tool that could quantify the leak, not just find it. And we did it by building on top of the technicians' existing process, not by disrupting it. The result was a patented solution that was immediately adopted, because it was built with and for the end-user.

The Lesson: Fall in Love with the Problem

This story is the foundation of my entire perspective on AI. It’s not about finding a place to use computer vision or a large language model. It's about finding the "soap bubbles"—the ingenious, human-centered processes that already exist—and asking, "How can AI make that better, faster, or smarter?"

AI that actually works is always a bridge between human expertise and machine efficiency.

Building a successful AI product team isn't about hiring the data scientists with the most impressive credentials. It’s about building a team that has the humility to go into the field, listen to the experts, and respect the processes and people that work.

AI governance isn't just a high-level review board; it's an on-the-ground process that asks, "Does this solution actually help the person doing the job?"

As I continue to write here, this is the theme I will return to again and again. The future of AI in energy and other critical infrastructure won't be defined by the most complex algorithm. It will be defined by the most creative, empathetic, and practical applications of those algorithms to solve real, tangible problems.